Zhou, Sean Xiang, Chen, Kevin Hongfan

Featured Faculty

Zhou, Sean Xiang

Professor

Chairperson, Department of Decisions, Operations and Technology

Director, Centre for Supply Chain Management

Director, Centre for Supply Chain Integration and Service Innovation, Shenzhen

More in Globalisation ...

Safeguarding supply chains in fragmented world

• 6 mins read

In the age of unprecedented uncertainty, supply chains are under constant peril and duress. How can companies mitigate risks and build resilience? A new CUHK study offers some answers

Intricately woven supply chains spanning across the world are susceptible to disruptive events. Many cases have pointed out that the disorders in a part of the globe cause disaster elsewhere for delayed shipment, shutdowns in factories, and ultimately financial loss.

Just a couple of years back, the lockdown in China caused havoc beyond its borders as companies in the US, Australia, Vietnam and other countries were struggling to source crucial components and materials for their manufacturing. Not just that, a 2021 winter storm in Texas caused many chip manufacturers a power outage, forcing Korean giant Samsung to cut their production.

Furthermore, since 2020, the US Commerce Department has tightened exports to China’s largest chip manufacturer, Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation or SMIC, exacerbating what the analysts call “decoupling”. With the trade tensions ramping up, one can only assume this trend will accelerate.

“During the COVID-19 pandemic, about 75 per cent of US firms were reported to suffer from supply chain disruptions and 62 per cent of them experienced delays in receiving goods from China in 2020,” says Kevin Chen Hongfan, Assistant Professor of the Department of Decisions, Operations and Technology at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) Business School.

With the background of current geopolitical tensions, companies worldwide are reshuffling their supply chains to survive the competitive market. This increases the likelihood of disruption with suppliers at many different times. “As its supply chain gets longer because of outsourcing or offshoring, a firm will very likely experience disruption at different tiers of suppliers at different times,” Professor Chen adds.

Therefore, developing a way to be resilient in the face of the calamitous effects of disruption becomes imperative. Given this urgency, Professor Chen and the department chair, Professor Sean Zhou, along with their doctoral student Zhu Yixin, delved deeper into this issue to provide some insight.

Centralised vs. decentralised networks

The study titled Supply disruption in multi-tier supply chains: Competition and network configuration examines expected profit, output quantity, and output variability in supply chains. The researchers found that positive and negative impacts depend on the type of disruption, completeness of the manufacturing network, and whether the supply chain is centralised or decentralised.

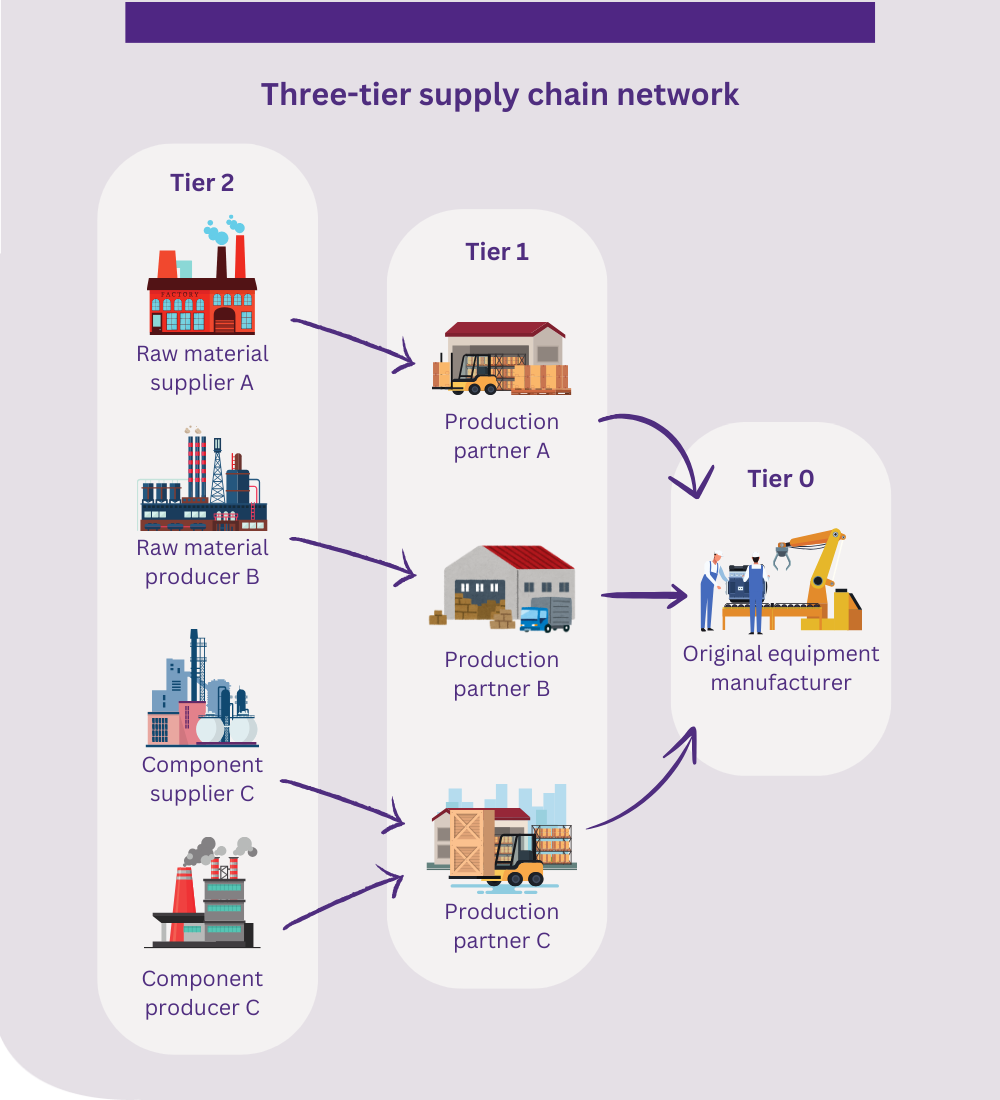

Using a combination of theoretical modelling, analytical techniques, and numerical simulations, researchers examined supply disruption in a three-tier supply chain network. Tier-2 suppliers obtain raw materials, produce, and then feed tier-1 suppliers, which in turn, manufacture and sell to tier-0 original equipment manufacturers (OEMs), which produce parts and equipment to be marketed by other companies.

The result suggests that supply chains are prone to disruption whether they are centralised or decentralised. A centralised supply chain means the entire supply chain is owned and jointly managed by OEMs, while in a decentralised one, each part is run by an independent firm that decides on its production quantity to maximise profit.

The disruption in tier-1 suppliers was found to result in lower profits and output in the centralised supply chain, yet this is reversed in the decentralised chain if the successful production rate and material cost are low. A strategic implication for OEMs is that if they allocate less resources to risk mitigation, they ultimately spend more on tier-1 suppliers.

The researchers note that the supply chain is not always complete, as not every location can be supplied by the same firms. “This network structure depends on how manufacturers choose their suppliers, which is a long-term process with strategic considerations such as business environment, infrastructure, labour supply, geopolitics, tax and tariffs,” says Professor Chen.

For instance, Chinese car maker Greatwall and US automobile manufacturer Ford have established their own unique tier-1 and tier-2 supplier bases, apart from their common supplier bases. Having more suppliers at hand is an absolute necessity in today’s fragmented markets.

Managing risk in fragmented worlds

Network incompleteness is frequently attributed to political tensions, making for trade barriers among firms globally. In an ideal world, goods would move seamlessly across borders, but when the network between tiers is incomplete, the missing links can cause disruption.

“As its supply chain gets longer because of outsourcing or offshoring, a firm will very likely experience disruption at different tiers of suppliers at different times.”

Professor Kevin Chen Hongfan

“In this incomplete network, when disruption occurs in its supply chain, it is costly, if not impossible, for a firm to immediately find an alternative qualified supplier to avoid the impact of the disruption,” Professor Chen explains. “Instead, risk mitigation actions, including diversifying the supplier base, should be planned long before the event occurs.”

The study found that the negative impact of disruption (measured by the profit loss relative to the case without disruption) can reach 15 per cent in the complete network and 18 per cent in the incomplete one. In short, a centralised supply chain may not protect from the chaos.

“The centralised supply chain may not necessarily be more robust than the decentralised one when facing disruption risk, as we might expect. Meanwhile, the network incompleteness impacts the decentralised supply chain profit more than that of the centralised one,” Professor Chen adds.

Putting out supply chain flames

More understanding can be gained when examining disruption and the importance of supply chain visibility. This could be especially helpful for firms that wish to proactively manage risks through monitoring, establishing a network of back-ups, and creating a surplus inventory.

The study found that network incompleteness would amplify the negative impacts of disruption, especially when a reliable well-known firm with a strong track record is located in an unreliable tier of the supply chain, which is prone to business disorder and supply chain disturbance.

In terms of profit impacts within tier-1 disruption, an incomplete upstream network in a centralised supply chain makes a higher profit than an incomplete downstream network, while in a decentralised chain, an incomplete downstream network generates a higher profit only when disruption risk is high.

In centralised and decentralised supply chains, output is more stable under tier-1 than tier-2 disruption, and network incompleteness amplifies the output variability. The researchers assert that effective supply chains need to have a higher flexibility of downstream firms than upstream firms, except when disruption risk is higher, and the supply chain is decentralised.

“By understanding how disruption position and network configuration affect output variability, supply chains can make informed decisions to improve their output stability when needed,” says Professor Chen.

Firms have many types of vertical integration in their supply chains, and ultimately, resources are limited. In an unpredictable era, building flexible sourcing relationships across several tiers of the supply chain is essential, or as the popular proverb goes, “Don’t put all your eggs in one basket”.